The Chinese populace of УлшжжБВЅ dates back probably before the 1870 census that lists 20 Chinese within its borders. By 1880, over 1,600 were living and working throughout the territory. Many arrived as laborers for the railroad, laying rail lines over the scorched desert, through mountain passes and across arid grasslands.

Of those 1,600 individuals, about 300 lived in and around УлшжжБВЅ.

According to an 1884 article in the УлшжжБВЅ, УлшжжБВЅ boasted т11 Chinese stores тІ 11 laundries тІ one saloon keeper, two doctors, two druggists, seven restauranters and one gambling house keeper.т It was a viable community.

In addition, Chinese gardeners grew crops on the outskirts of town near the Santa Cruz River. Hauling their wagons laden with fresh fruits and vegetables into the bustling settlement, they sold their produce house to house.

People are also reading…

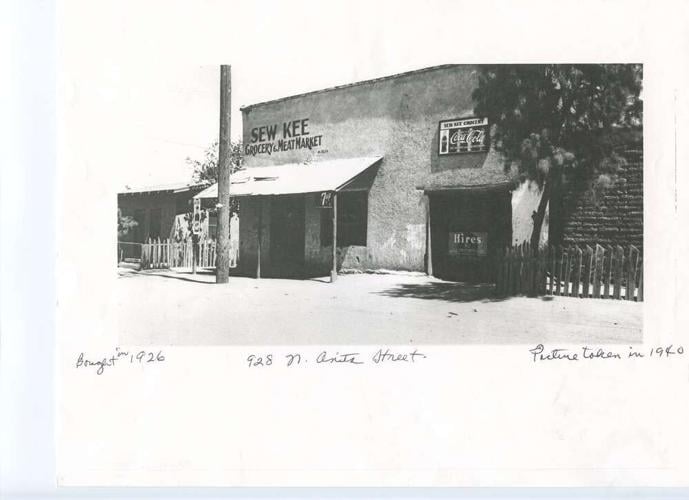

Sew Kee Market

Ling Kee Low arrived in УлшжжБВЅ around 1891, working his way across the country building miles of rail lines. He must have liked the looks of УлшжжБВЅ as he decided to stay, and by the following year, he had opened a grocery store on Convent Avenue.

He sent for his son, Sew Kee, who was still living in China, to help with his grocery business. Over the next few years, Sew Kee may have made several trips back to China, as in June 1912, he married Lee Shee in Canton, China, where she had been born on Aug. 6, 1893. The couple had at least two children before Lee Shee Low arrived in УлшжжБВЅ in 1921.

One-year-old Loy Low traveled with his parents to his new home in America, but another child was left behind. Daughter Low Sui Kum Chan remained in China to care for her aging grandmother. It would be 10 years before Lee Shee saw her daughter again.

Lee Shee and Sew Kee started their own grocery business, Sew Kee Grocery & Meat Market on Anita Avenue in what is now the Barrio Anita district.

Over the ensuing years, Lee Shee had five more children. Along with Low Sui Kum Chan (still in China) and son Loy, who came to the U.S. with his parents, the family next added son John. Daughters Mary and Somei bridged the gap between two more sons, Sunny and Joe.

Since the majority of the storeтs clientele were Hispanic, and most of her neighbors of Mexican ancestry, Lee Shee soon picked up the Spanish language along with English.

Local laws and bills prevented Chinese residents from living in designated areas of cities and towns throughout the country. Certain parts of УлшжжБВЅ were off limits to the Chinese populace. According to one of Lee Sheeтs children, тIf you were not white, you couldnтt buy property on the east side of Campbell (Avenue).т There were also rules prohibiting marriage between Chinese and Anglos.

The Low family lived in the same building that housed the Sew Kee Grocery Store.

Lee Shee and Sew Kee made at least one trip back to China in 1931 when their daughter, Low Sui Kum Chan, married. She remained in China, and many more years would pass before mother and daughter reunited again.

Lee Shee Low and son John in front of the store.

Tragically, Sew Kee died in 1937 at the age of 43. Lee Shee was left on her own to care for her children and run the grocery store. At the time of Sew Keeтs death, the childrenтs ages ranged from 3 to 17. Those old enough helped in the store.

A petite woman, less than five feet tall, Lee Shee brooked no nonsense from merchants as she ordered supplies, stocked shelves, rang up sales and swept the shop, trying to keep the store profitable for her growing family. She was known throughout the neighborhood for her business acumen and fair treatment of her customers. The older children helped out after school and on weekends with the littlest ones quickly learning the trade.

In 1952, the grocery store name changed to Low Grocery. By now, Lee Sheeтs older children were an integral part of the business, and it might have been one of them who suggested the name change. In addition, a delicatessen may have been added at this time.

In 1960, at the age of 63, Lee Shee became a U.S. citizen.

She celebrated her 80th birthday (a monumental event within the Chinese community) with an elaborate party at Four Seasons Restaurant, organized by her children to honor their hard-working, energetic mother. Peking duck, thousand-layer bread, squab and birdтs nest soup were just a few of the delectables on the 10-course meal menu.

According to one newspaper article, тEach guest at the party also received a bowl and set of chopsticks as souvenirs of the occasion. Both bore the Chinese symbol of longevity and the color red for good luck.т

The article lists six of her children attending the event. Daughter Low Sui Kum Chan was still in China.

Happy birthday, УлшжжБВЅ. See a few important events in УлшжжБВЅ's history.

Lee Shee continued to manage the grocery business until 1974, when she finally retired and turned the operating and day-to-day duties over to her children. Some had married and had families of their own. She was known as тPopoт to her grandchildren, the Chinese word for тgrandmother.т

In 1980, one of Lee Sheeтs granddaughters married at УлшжжБВЅтs УлшжжБВЅ Inn. To add to the festivities, Low Sui Kum Chan, Lee Sheeтs first child, traveled from China to УлшжжБВЅ to celebrate the occasion. Almost 50 years had passed since mother and daughter had last seen each other.

The following year, on April 2, 1981, Lee Shee died at the age of 87. She had endured her share of difficulties during her long life and worked hard in a small grocery store in the heart of УлшжжБВЅ that held her family together through years of struggle and separation.

The original Sew Kee grocery store building still stands today.

Jan Cleere is the author of several historical nonfiction books about the early people of the Southwest. Email her at Jan@JanCleere.com. Website: .